Did a train accident cause an off-campus lunch ban?

Train tracks at the intersection of Cedar Hills and Broadway.

If you’ve walked through the halls during passing time, you’ve probably overheard the debate many times. Why can’t Beaverton High School students leave campus for lunch? There seem to be a few theories floating around, but the most common is about a train accident.

It goes something like this: A Beaverton student was killed crossing the train tracks during the lunch break. The school, worried about safety, closed the campus.

This theory has become a school legend, serving as justification for the lunchtime rule imposed on us by the administration. Although embraced by many, the available facts were sparse.

So, a student may have been killed in a train accident, but what else occurred? The connection between this and the closing of campus lunches was tenuous with the few facts available. The Hummer set out to research the events that led to the closed campus policy and the truth behind the train accident rumor.

The BHS campus wasn’t always closed. In the 1980s, students could leave the campus for lunch. College and Career Counselor and BHS alum, Carrie Matsuo said, “You just had to be back in time. You didn’t need any special permission, you didn’t have to have a note. You could just go have lunch.” The city was much smaller than it is now, but some popular options included Mexicali Express, Beaverton Deli, and McDonald’s. Sometimes students would even drive to other schools during lunch break.

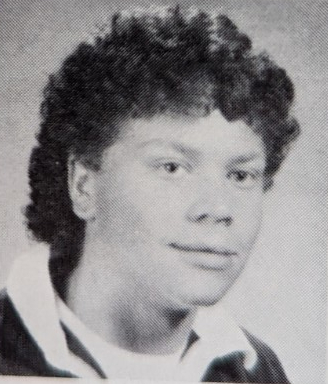

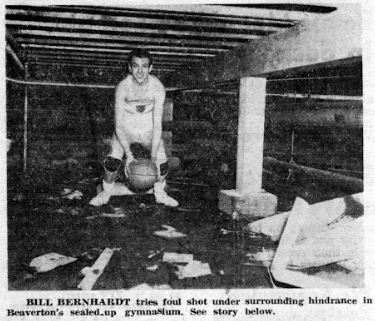

In the early afternoon of Wednesday, October 15, 1986, Dean Stoloff and his friend Douglas Drey were returning from lunch at Mexicali Express. At the time, Beaverton School District (BSD) students were allowed to leave for lunch if they had signed permission from the parents on file with the school. As they were crossing the tracks at the intersection of Cedar Hills and Broadway, Stoloff was struck and dragged underneath a train engine. Stoloff died shortly before 5 p.m. later that day. The train was going under the legal limit of 30 miles per hour and using its whistle. According to an Oregonian article from October 16, 1986, “the youths apparently did not hear or see the oncoming engine…Drey came very close to being struck.”

Stoloff was only 17 years old. Originally born in South Africa, Stoloff moved to Beaverton when he was in elementary school. He was a member of the school tennis team and was described as “happy-go-lucky and easy-going,” by Principal Bruce Weitzel in an article by the Beaverton Valley Times.

This also wasn’t the last time Beaverton would see an accident involving a train. On the Monday night of January 16th, 1989 a 15-year-old boy was struck after walking into the side of a train at 8:30 p.m. The incident happened on the same tracks but near the intersection of Watson Avenue and Broadway. An Oregonian article stated that the boy was taken to the hospital and listed in fair condition.

These two incidents along with the serious injury of a car salesman crossing the tracks prompted the city to invest in fences diverting students towards safe crosswalks. City councilors were persuaded by the results of a two-day survey conducted the previous year, showing “more than 200 students crossing the tracks in mid-block.” New plans would include “two wrought-iron fences, each eight feet tall” to discourage crossing mid-block and to funnel students to the controlled intersection at Cedar Hills Boulevard. The $80,000 cost was split between the city, BSD, and the Southern Pacific railroad.

Beaverton wasn’t the only school with tragedy occurring during lunchtime. One day short of a year after the death of Stoloff, Sunset High School junior Mason Rosa III died in a noontime car crash. At the time, the BSD rule was that no student could leave the campus in a motor vehicle during school hours except for exceptions like doctor’s appointments (even then, written parental permission was needed). Yet many students snuck out to eat lunch in the shopping areas near Sunset. School district officials admitted it was hard to enforce the policy 100% of the time. The Oregonian Headline read: “Fatal car wreck by Sunset student unveils rules dilemma.” Seven years later that dilemma would be resolved.

In the 1980s, Beaverton had three high schools in the district: Aloha, Sunset, and Beaverton. Each had two junior high schools that fed straight into the high school. These junior high schools contained 7th, 8th, and 9th graders. When Westview High School opened in 1994, it seemed like a good time to mix up the system. Ninth graders were brought into the high schools and sixth graders were brought into middle schools. Along with that came closed campuses for all students in the district.

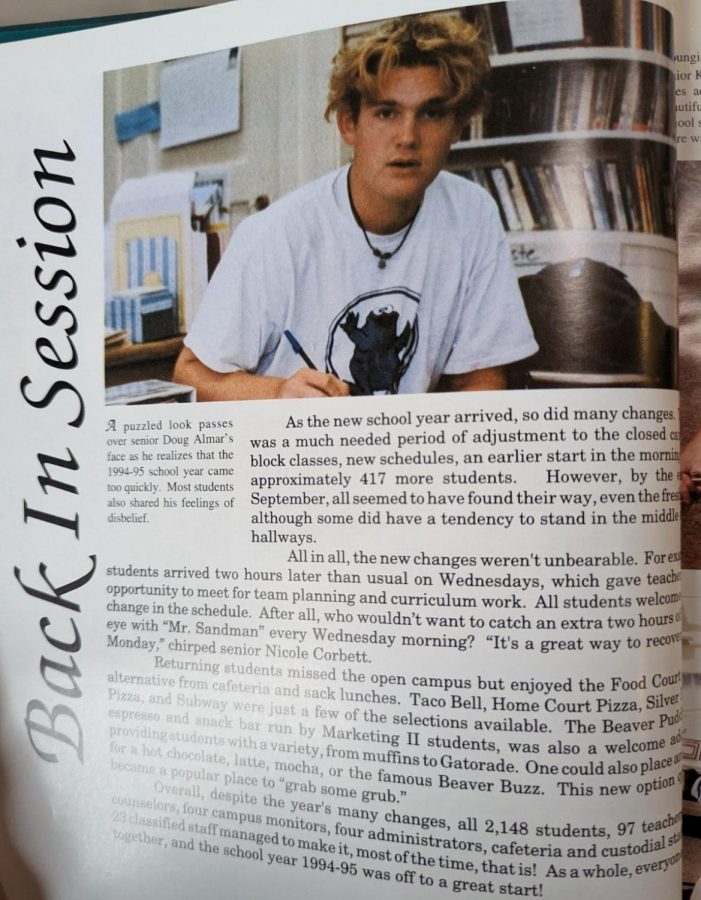

Social studies teacher Peter Edwards started his teaching career at Beaverton in the 1990s. He believes it was more than a coincidence that campuses closed that year. The district probably wanted to assure the parents that their kids would be safe as high school freshmen. Instead of going to middle school, 9th graders were going to a place “where [students] have cars and drive around, and people go off campus. I do think that when they looked at it, they said, ‘well, we’re bringing ninth graders up and we’re going to have more younger kids there. It might make the parents feel better if we told them the campus was closed.’”

While it was easy to convince the parents, not everyone was happy with the decision. The seniors that had just last year been allowed off campus were very unhappy with losing the privilege. “First of all students didn’t like it,” said Edwards. “Students with cars didn’t like it, students who liked to go to McDonald’s for lunch didn’t like it, students who wanted to smoke cigarettes didn’t like it.”

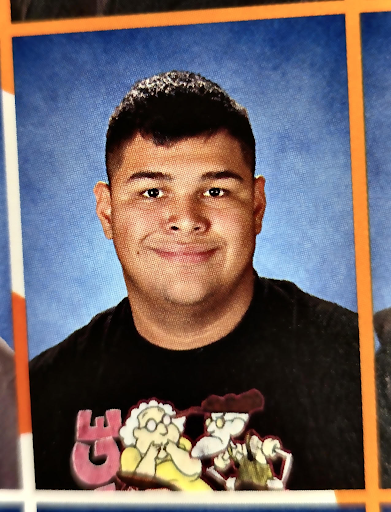

The new freshmen at the school were resented by the upperclassmen. “Everyone hated us, that’s for sure, ‘cause we ruined everything,” said Charles Chung, a current BHS English teacher, and member of the first class of 9th graders.

The school tried to prevent students from leaving campus by hiring campus monitors and putting gates around student parking lots. Students still managed to find a way around the gates either by parking on side streets, walking from school, or finding more creative ways to get out. CTE and Health careers students were still allowed to leave the campus for their programs. Security would have to open the gates for these students.

“I was part of health careers, so I may or may not have leveraged that a little too many times to get off campus,” Chung recalled. “I would say I had to go to my rotation… I didn’t have a rotation and went off campus.”

Over time, the gates became the symbol of the closed campus – and a target for angered students. Edwards remembered students stealing the gates as a senior prank. “They were big, big, heavy metal gates. They removed the gates, stole them, to show their attitude about the closed campus.”

Chung confirmed that they really hated the gates. His class, the class of 1998, even wore graduation t-shirts that read “Breaking the Gate in ‘98.”

Throughout the 1990s, school campuses across the country continued to close their lunches at a steady rate. Open campuses went from the norm to an anomaly. A Washington Post article from 1999 confirmed this: “As concerns about traffic, troublemaking and other dangers beyond school walls have grown, more schools have ended their “open campus” policies, often with the support of parents and communities.”

Today, the closed campus is not a controversial policy. It’s listed in the rules of the Student & Family Handbook as an offense at every Beaverton School District school. Code 7 of the Student Code of Conduct prohibits leaving campus. “Leaving school property without approved prearranged permission on file in the school office.”

Most students acknowledge the rule, although they may not respect it. Food from Dairy Queen and pizza boxes mysteriously show up in Beaver Lodges. As Chung said and many students know, “You find a way to get around it.”

Samson is a senior at Beaverton High School who writes and edits articles for The Hummer. In his free time, he enjoys playing soccer and racquetball.

KK • Jun 26, 2023 at 12:39 pm

I had English class after lunch with Dean and he was a good guy. When he didn’t come back that day, we were all in shock. Tons of BHS students walked over those tracks daily for lunch. At the time we didn’t need permission to walk or drive anywhere. Looking back, I don’t understand how frieght trains were able to go right through the middle of downtown Beaverton, regardless of a “legal” speed with no barriers. Closed campus was a change, and one we understood was needed. For anyone upset today about a closed campus, I would say to just accept it as fact and move on. You can drive or walk wherever you want before or after school. You will have plenty of years to enjoy your freedom of spontaneous lunch choice when you have graduated. The adults who make these decisions come from a place of trying to protect you, regardless of the motivation. In our case, we all lost a classmate who would have been fine if he just ate a sandwich in the hallway or cafeteria. And we did just that, from then on, for Dean.

GC • Aug 2, 2023 at 10:50 am

That is a fascinating way to consider the issue, and I’ll try to address fairly the logic of it. As a prelude, I will make the mutual concession that minors are entitled to protections, not rights, and that it is often best to leave decisions to those with more life experience. That said, there are a few points worth considering here.

Firstly, you use the argument of accepting administrative rules as a fact given that they only have a minor impact for a short period of time. As a way to avoid being resentful, I think this is a fine tact to take. On the other hand, if one were to apply this logic to, say, the rest of issues in their life and with government, resentment and stagnation are generally the only results. Simply ignoring things the broad population disagrees with allows administrators to enact policies which ultimately restrict the class in question. Restriction which is unfair (here, you decide whether or not freedom of movement is age-appropriate) reduces respect for the rules themselves, and individuals will begin breaking rules with no notice to the government. As could be seen with prohibition, certain things, when unregulated, can get out of hand. As a result, now, students leave campus in violation of the rule and the expectations of security, and attendance overall is at an all-time low. You have said yourself that, “tons,” of students crossed the tracks without issue, and there has been rumor that the killed party was under the influence. It is, after all, very hard to miss an oncoming train. Now, many students continue to cross the tracks without issue. Perhaps the foolish behavior of one should not be evidence enough of an activity’s unsafety. This brings us to the next point.

In citing the adults’ motivation of protection, you imply that the decisions made from a standpoint of good intentions should be readily accepted, as you focus on the adults making the decision as opposed to the benefit of the decision itself. As I said in the opening, I will agree that adults tend to be better decision makers than seventeen-year-olds, and yet those adults are not the ones going to school, or leading teenage lives. In the old model, the assessment of risk was left up to the teen themselves, and it seems a question which isn’t hard to answer. Obviously, crossing train tracks has inherent and obvious dangers, but students were able to weigh whether or not it was worth it to them to have access to food. I would also like to point out, as well, that leaving campus does not have to involve crossing train tracks. Additionally, if the argument is made that students can govern their actions outside of school hours, why on earth would that change between 7:45 and 2:30? Perhaps I’m not fully understanding your position.

In the end, what this comes down to is a proposition of value. Do you value fostering independence, or do you value protection. Personally, I’m more convinced by the psychological literature that giving people control over their own lives is nearly essential to happiness, and I don’t consider constant protection an end worth sacrificing for. When I was in elementary school, the new policy became that running wasn’t allowed on blacktop because it was too dangerous. This, now, is an extension of that doctrine. Understand, by reducing the control and risk people have in their lives, you prevent them from learning how to solve problems on their own, and create a condition reminiscent of learned helplessness. And people become dependent.

Finally, I would like to say that I totally understand and acknowledge where you’re coming from. Losing someone, especially a classmate at that age is incredibly traumatic, and if I were in your position I would likely feel the same. The problem with these issues is that when you extend their precedent good intentions can become bad results. Personally, a closed campus means I waste less money on fast food. But I believe others are entitled to control this part of their lives, and that, fundamentally, is why I disagree.