As climate change concerns rise, BHS must take action

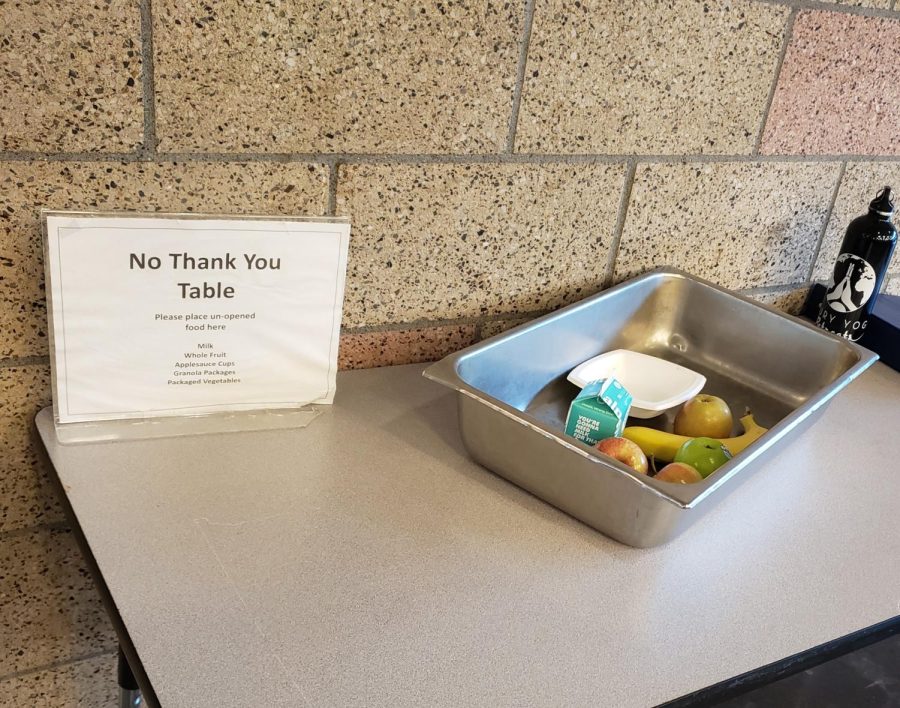

The No Thank You Table in the cafeteria is one of the few options BHS students have to prevent their unwanted food from being wasted.

Our impact on the planet grows greater every day and there is little being done to stop it. The last seven years have been the warmest on record, and this is just the beginning of the colossal impact of global warming. Currently, almost one million species are at risk of extinction by climate change.

Food waste is one of the greatest threats to our planet, accounting for almost 8% of all greenhouse gas emissions. This may seem small, but its carbon footprint is greater than the airline industry—and our school is contributing to the problem.

According to K-12 Dive, “A new World Wildlife Fund report estimates U.S. school food waste totals to 530,000 tons per year and costs as much as $9.7 million a day to manage, which breaks down to 39.2 pounds of food waste and 19.4 gallons of milk thrown out of school per year, based on results from the forty-six school samples across nine cities”

Because school lunch is free this year, more students than usual are benefiting from the meals, which means there is more waste than ever. All of the food waste is thrown into the trash due to a lack of composting system and difficulty accessing recycling bins.

This waste ends up in landfills, resulting in large amounts of methane, which is worse than CO2. Further, almost 70% of the planet’s available freshwater is used for agriculture, meaning food waste impacts water usage as well. In short, throwing away food discards the time, energy, and resources it took to make. The best way to solve this problem is to eat all you take, but realistically, most students won’t do that. The second-best solution is to compost.

Beaverton High School has no compost bins available for the students, though there is a bin in the cafeteria for unwanted food—mostly produce. This results in a surprising lack of options for students who want to make a small difference. If there were composting systems available at school, BHS would be able to save resources and help the environment by reducing methane emissions. A typical compost bin only costs $25-30; assuming the school bought four to place around the cafeteria and student center where students normally eat, it would only cost $120—a small piece of the District’s budget.

While managing the compost would take some extra time, there are options to dispose of it, such as by talking to organizations like ShareWaste who find people who want the compost. A community garden could also be built alongside BHS’ upcoming remodel, which would serve as another location to use the compost and provide locally sourced food available that could be used for lunches, forming a healthy circle of waste and recycling.

“I honestly think it’s a really good idea,” said junior Mikayla Sinclair, “but actually doing it might be a challenge as students might not fully participate in it. It might be a little hard to understand. I do think it could work.”

To make a change, you have to put in the work. It can be as simple as sorting some leftovers.

Natalie is a senior and Staff Writer/ Social Media Editor for The Hummer. In her spare time, she enjoys hiking, baking, and hanging out with friends.

Anouk is a senior who writes and edits articles, takes the occasional photo, and helps everything run in the background.

![Social Media has contributed to the rise of the incel movement [Photo via Wikimedia Commons under Creative Commons license].](https://beavertonhummer.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Man_on_a_smartphone_Unsplash-600x400.jpg)

!["About The Weather" was released in 2023 as the first album by Portland emo band, Mauve. [About The Weather Album Cover]](https://beavertonhummer.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/AboutTheWeather.jpg)

Angela • Feb 19, 2022 at 9:41 pm

It’s true and easy to do. We all need to do our part.